Kwa wale wafia dini, huyu hapa chini ni mwarabu mkristo, mwanasanyansi nguli, na ni mhadhiri wa chuo kikuu na anautetea uarabu wake kwa kuonyesha historia ya waarabu katika

sayansi na dini ya kiislamu.....

Kama una bando la kutosha fungua macho , kama huna niambie nitakutumie na ya kutolea...

Sio unashoboka na msalaba wa rozari uliokufumba macho , wakati wanaojielewa wanautetea utaifa wao bila kujali kuwa misukule ya ngano za kale.....

This is enough to light up the dark ages, ignite the Renaissance, and inflame modern science. The evidence is in the nouns: algebra, alchemy, alcohol and even the capital letters of astronomy and history, Aldebaran and Avicenna and the

Almagest of Ptolemy.

So far, so familiar. But Jim al-Khalili's book does more than just enrich a familiar narrative: it brings alive the bubbling invention and delighted curiosity of the Islamic world. The Greeks certainly provide the thread for the story, but from such thread the Ummayyads and Abbasids wove their own astonishing fabric of discovery and enlightenment. Empires are built on bloodshed but survive on know-how. "The ink of the scholar is more sacred than the blood of the martyr," said the prophet Muhammad, and the empire founded in his name had a communication problem to solve before it could build its knowledge economy.

Persian or Pahlavi texts had to be translated into Arabic, among them studies of astrology, which may originally have been based on mathematics texts in Sanskrit. The new empire also needed Arabic versions of texts on geometry, engineering and arithmetic; it clashed with the Chinese, and from prisoners learned the art of papermaking. The first paper mills were established in Baghdad at the end of the eighth century: dyes, inks, glues and bindings followed. During and after the reign of Harun al-Rashid, the fabulous caliph of the so-called

Arabian Nights, Persian, Arab, Christian and Jewish scholars all began to translate and publish medical and mathematical texts from Greek and Syriac as well as Persian and Indian scripts.

Around this time, Geber or

Jabir ibn Hayyan the alchemist composed the

Kitab al-Kimiya, a systematic examination of the nature of matter, which in 1144 would be translated into Latin by Robert of Chester as the

Liber de compositione alchimiae. From Jabir we gain the word alkali, the distilling apparatus known as an alembic and – says Al-Khalili – perhaps even the word gibberish. Later Arabic texts delivered words we still use today: amalgam, borax, camphor, elixir. Whether Jabir counts as scientist or alchemist is an open question: within a generation, real science, intense scholarship and a palpable curiosity about the physical world began to emerge. Harun's successor Al-Ma'mun is linked with the founding of the House of Wisdom, a library, academy and translation factory that may have become at the time the largest repository of books in the world. Polymaths produced maps that showed the Indian Ocean and the Atlantic as open bodies of water, and tried to crack the meaning of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs; they composed star charts, and adapted the Hindu number system to deliver the numerals we now use every day.

Not all Al-Khalili's heroes were Arabs:

Omar Khayyam calculated the length of the solar year to 11 decimal places and composed in his native Persian a famous

Treatise on Demonstration of Problems in Algebra, as well, of course, as those lines about the jug of wine, the loaf of bread and thou. Aristotle, too, lives on in this story: he appears in a dream to a caliph's son, and he fascinates generations of Islamic scholars. They were also people of their time. They accepted the theories of the four humours and the geocentric universe. But Ibn al-Haytham's

Book of Optics pioneered the study of refraction and applied mathematics to a theory of vision; his successor Ibn Mu'adh used Euclidian geometry to calculate the height of the atmosphere at 52 miles (it is about 62 miles).

The tradition of inquiry and scholarship reaches far beyond Baghdad: to Samarkand and Bokhara, to Cairo and Cordoba. In the 10th century, in Andalusia, Al-Zahrawi devised the forceps, speculum and bonesaw, pioneered inhalant anaesthetics in the form of sponges soaked with cannabis and opium, and even described the first syringe. Ibn al-Nafis in the 13th century anticipated Harvey and described the pulmonary transit of the blood from the right side of the heart, via the lungs, to the left.

Al-Khalili is a Baghdad-born British physicist: his command of Arabic and mathematical physics invests his story with sympathy as well as authority. He is careful to put Arabic science in its context; he tries not to claim too much for his heroes and his attention to detail and fairness is rewarding. The metaphor of science as a relay race is exposed as unsatisfactory: cultures overlap, enrich and stimulate each other, and 10th-century Arab scholars greedy for understanding form a community with 16th-century Elizabethans or 21st-century Cambridge dons. The easy equation of Islam and wilful ignorance never made sense – empires are not sustained by ignorance – but even in the 11th century, the rationalists felt it necessary to defend reason.

The Persian

Al-Biruni, who measured the height of a mountain and the angle of dip of the horizon to calculate the circumference of the planet to within an accuracy of 1%, warned that the extremist "would stamp the sciences as atheistic and would proclaim that they led people astray, in order to make ignoramuses of them, and to hate the sciences. For this will help him conceal his own ignorance, and to open the door to the complete destruction of the sciences and the scientists."

He might have been talking about the mullahs of modern Tehran, or the ranters of the US religious right. In the end, Arabic science did falter. The flame was picked up by Copernicus and Galileo, by William Harvey and Isaac Newton. In 2005, scientists from 17 Arab countries produced 13,444 scientific publications. Harvard University alone that year produced 15,455.

The discovery of the sine law of refraction is credited to Ibn Sahl who first proved the law in 984.

- "Snell's Law" (or "Sahl's Law" as it should be known) is arguably one of the most important laws in physical optics today, and traces it's origins back to 984, when it was first discovered by Abu Said al-Ala Ibn Sahl of Baghdad (940—1000),[1][2][3][4][5] in his manuscript "On the Burning of Instruments".[6]

- Naturally this important and crucial discovery has been challenged by some European authors,[n. 1] who would like to claim that it was discovered in Europe; however modern historians of science credit ibn Sahl with the discovery.[n. 2] However, it should be noted that this revelation took centuries to come to fruition, as Ibn Sahl was only credited with the discovery in 1990, when French scholar on the history of science, Rashed Roshdi, located his manuscripts in Tehran, Iran; which proved that it was actually the eponymous scientist who first came up with the concept and subsequently discovered the law.[7]

- Traditionally, the law was previously credited to the Dutchman, Willebrord Snellius (1580—1626), though he never claimed to have discovered it himself, as his manuscript was never formally published.[8] This overall historical confusion on who found the law of refraction first was down to the fact that knowledge of Sahl's work was simply lost as his pupil, Ibn Al Haytham (965–1040), rejected his teachers original work and so it was long assumed that Ibn Al Haytham did not know of the law, when he actually did; thereafter taking the Europeans 637 years to rediscover Sahl's correct law.[n. 3]

Ibn Sahl's law with Arabic annotation's translated.

- One of the most important applications of the law are in the design of eye-glasses, which bend light in order to focus rays to the wearer's eyes.[9] Indeed, the law was being used by Ibn Sahl himself when he was designing lenses in the 10th century;[10] and could have possibly used them to correct eye sight; later the Europeans began designing eye lenses in the 1350s, using convex lenses, and in the 1450s concave lenses.[10]

- This law is also important when designing telescopes and microscopes.[9] Indeed, without the law, the development of telescopes would not have moved forward.[11] It is also possible that the invention of the telescope may have been invented several times over, including during the Islamic Golden Age, well before the invention in 1608 became widely popular in Europe.[10] The law is so important and so vast that it is even used in military applications for the design of stealth fighter jets;[12] where the surfaces of such planes reflect incident radar pulses away from themselves based on the physics behind the law, but not in the direction of the pulse radar equipment so as to give away their position.[12] Using this law further, besides deflecting the classical sinusoidal waves, it also deflects the Dirac delta function.[12] Thermal noise is also able to be deflected if the law is followed correctly.[12] However it should be noted that further designs, or later developments in radar technology are now able to overcome the practical aspects of the law; thereby circumventing it.[12]

The principal of total internal reflection.

- Another important result of Sahl's work is that of optical fibres. These instruments are used to transmit converted electrical signals to light energy,[13] across large or small distances with minimal loss. Compared to conventional methods, in those of copper fibres used to transmit the same signals, efficiency is low, and there can be a significant amount of loss.[14][15] The most important industry where optical fibres are used currently is in internet technology, which contribute to the increase of download speeds.[16] Light, as a physical quantity, tends to travel in straight lines,[17] and it is extremely difficult to bend given the speed at which it travels, which is 300 million meters per second[17] (though it can be done, simply not without meta-materials,[18] unless black holes are accounted for).[19]

- In optical fibres, light is deliberately redirected in straight lines by bouncing it off at a particular angle.[20] This particular angle is the angle that is greater than the critical angle, which is otherwise known as "total internal reflection".[21] Importantly this angle can be calculated by the Sahl's law of refraction.[22]

- The photonics industry, of which fibre optics transmission is a part of, is as a result extremely lucrative, worth an estimated $721 billion dollars.[23] However, historical chronic mismanagement of fiber optics has remained problematic; despite firms having invested $90 billion dollars (1997—2001), only 2.6% of consumers used the technology.[24] Sahl's work therefore remains to be fully exploited

Early Caliphates[edit]

7th century

An illustrated headpiece from a mid-18th-century collection of

ghazals and

rubāʻīyāt, from the

University of Pennsylvania library's Lawrence J. Schoenberg Collection

[6]

8th century

- Arabesque: The distinctive Arabesque style was developed by the 11th century, having begun in the 8th or 9th century in works like the Mshatta Facade.[8][9]

- Astrolabe with angular scale : The astrolabe, originally invented some time between 200 and 150 BC, was further developed in the medieval Islamic world, where Muslim astronomers introduced angular scales to the design,[10] adding circles indicating azimuths on the horizon.[11]

- Classification of chemical substances: The works attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan (written c. 850–950),[12] and those of Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (c. 865–925), contain the earliest known classifications of chemical substances.[13]

- Damascus steel: Damascus blades were first manufactured in the Near East from ingots of Wootz steel that were imported from India.[14]

- Geared gristmill: Geared gristmills were built in the medieval Near East and North Africa, which were used for grinding grain and other seeds to produce meals.[15]

- Modern Oud: Although string instruments existed before Islam, the oud was developed in Islamic music and was the ancestor of the European lute.[16]

- Sulfur-mercury theory of metals: First attested in pseudo-Apollonius of Tyana's Sirr al-khalīqa ("The Secret of Creation", c. 750–850) and in the works attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan (written c. 850–950),[17] the sulfur-mercury theory of metals would remain the basis of all theories of metallic composition until the eighteenth century.[18]

- Tin-glazing: The earliest tin-glazed pottery appears to have been made in Abbasid Iraq/Mesopotamia in the 8th-century.[19] The oldest fragments found to-date were excavated from the palace of Samarra about 80 kilometres (50 miles) north of Baghdad.[20]

- Panemone windmill: The earliest recorded windmill design found was Persian in origin, and was invented around the 7th-9th centuries.[21][22]

9th century

- Algebra discipline: Al-Khwarizmi is considered the father of the algebra discipline. The word Algebra comes from the Arabic الجبر (al-jabr) in the title of his book Ilm al-jabr wa'l-muḳābala. He was the first to treat algebra as an independent discipline in its own right.[23]

- Algebraic reduction and balancing, cancellation, and like terms: Al-Khwarizmi introduced reduction and balancing in algebra. It refers to the transposition of subtracted terms to the other side of an equation, that is, the cancellation of like terms on opposite sides of the equation, which the term al-jabr (algebra) originally referred to.[24]

- Automatic controls: The Banu Musa's preoccupation with automatic controls distinguishes them from their Greek predecessors, including the Banu Musa's "use of self-operating valves, timing devices, delay systems and other concepts of great ingenuity."[25]

- Chemical synthesis of a naturally occurring compound: The oldest known instructions for deriving an inorganic compound (sal ammoniac or ammonium chloride) from organic substances (such as plants, blood, and hair) by chemical means appear in the works attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan (written c. 850–950).[26]

- Chess manual: The oldest known chess manual was in Arabic and dates to 840–850, written by Al-Adli ar-Rumi (800–870), a renowned Arab chess player, titled Kitab ash-shatranj (Book of Chess). During the Islamic Golden Age, many works on shatranj were written, recording for the first time the analysis of opening moves, game problems, the knight's tour, and many more subjects common in modern chess books.[27]

- Automatic crank: The non-manual crank appears in several of the hydraulic devices described by the Banū Mūsā brothers in their Book of Ingenious Devices.[28] These automatically operated cranks appear in several devices, two of which contain an action which approximates to that of a crankshaft, anticipating Al-Jazari's invention by several centuries and its first appearance in Europe by over five centuries. However, the automatic crank described by the Banu Musa would not have allowed a full rotation, but only a small modification was required to convert it to a crankshaft.[29]

- Conical valve: A mechanism developed by the Banu Musa, of particular importance for future developments, was the conical valve, which was used in a variety of different applications.[25]

- Control valve: The Banu Musa brothers are credited with the first known use of conical valves as automatic controllers.[30]

- Cryptanalysis and frequency analysis: In cryptology, the first known recorded explanation of cryptanalysis was given by Al-Kindi (also known as "Alkindus" in Europe), in A Manuscript on Deciphering Cryptographic Messages. This treatise includes the first description of the method of frequency analysis.[31][32]

- Double-seat valve: It was invented by the Banu Musa, and has a modern appearance in their Book of Ingenious Devices.[33]

- Farabian theories: three philosophical theories of al-Farabi: the theory of ten intelligences, theory of the intellect and theory of prophecy.[34]

- Food chains: This was identified by al-Jahiz.[35]

- Glass manufacturing: Abbas ibn Firnas developed the process of creating glass from stones.[36]

- Lusterware: Lustre glazes were applied to pottery in Mesopotamia in the 9th century; the technique soon became popular in Persia and Syria.[37] Earlier uses of lustre are known.

- Hard soap: Hard toilet soap with a pleasant smell was produced in the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age, when soap-making became an established industry. Recipes for soap-making are described by Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (c. 865–925), who also gave a recipe for producing glycerine from olive oil. In the Middle East, soap was produced from the interaction of fatty oils and fats with alkali. In Syria, soap was produced using olive oil together with alkali and lime. Soap was exported from Syria to other parts of the Muslim world and to Europe.[38]

- Mental institute: In 872, Ahmad ibn Tulun built a hospital in Cairo that provided care to the insane, which included music therapy.[39]

- Kerosene distillation: Although the Chinese made use of kerosene through extracting and purifying petroleum, the process of distilling crude oil/petroleum into kerosene, as well as other hydrocarbon compounds, was first written about in the 9th century by the Persian scholar Rāzi (or Rhazes). In his Kitab al-Asrar (Book of Secrets), the physician and chemist Razi described two methods for the production of kerosene, termed naft abyad ("white naphtha"), using an apparatus called an alembic.[40][41]

- Kerosene lamp: The first description of a simple lamp using crude mineral oil was provided by Persian alchemist al-Razi (Rhazes) in 9th century Baghdad, who referred to it as the "naffatah" in his Kitab al-Asrar (Book of Secrets).[42]

- Minaret: The first known minarets appeared in the early 9th century under Abbasid rule.[43]

- Music sequencer and mechanical musical instrument: The origin of automatic musical instruments dates back to the 9th century, when Persian inventors Banū Mūsā brothers invented a hydropowered organ using exchangeable cylinders with pins,[44] and also an automatic flute playing machine using steam power.[45][46] These were the earliest mechanical musical instruments,[44] and the first programmable music sequencers.[47]

- Kamal: The kamal originated with Arab navigators of the late 9th century.[48] The invention of the kamal allowed for the earliest known latitude sailing, and was thus the earliest step towards the use of quantitative methods in navigation.[49]

- Observatory and research institute: The oldest true observatory, in the sense of a specialized research institute, was built in 825, the Al-Shammisiyyah observatory, in Baghdad, Iraq.[50][51][52]

- Petroleum distillation: Crude oil was often distilled by Arabic chemists, with clear descriptions given in Arabic handbooks such as those of Muhammad ibn Zakarīya Rāzi (Rhazes).[53]

- Programmable machine and automatic flute player: The Banū Mūsā brothers invented a programmable automatic flute player and which they described in their Book of Ingenious Devices. It was the earliest programmable machine.[45]

- Sharbat and soft drink: In the medieval Middle East, a variety of fruit-flavoured soft drinks were widely drunk, such as sharbat, and were often sweetened with ingredients such as sugar, syrup and honey. Other common ingredients included lemon, apple, pomegranate, tamarind, jujube, sumac, musk, mint and ice. Middle Eastern drinks later became popular in medieval Europe, where the word "syrup" was derived from Arabic.[54]

- Sine quadrant: A type of quadrant used by medieval Arabic astronomers, it was described by Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī in 9th century Baghdad.[55]

- Scimitar: The curved sword or "scimitar" was widespread throughout the Middle East from at least the Ottoman period, with early examples dating to Abbasid era (9th century) Khurasan.[56]

- Sugar mill: Sugar mills first appeared in the medieval Islamic world.[57] They were first driven by watermills, and then windmills from the 9th and 10th centuries in what are today Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran.[58]

- Early syringe: The Iraqi/Egyptian surgeon Ammar ibn Ali al-Mawsili invented an early syringe in the 9th century using a hollow glass tube, providing suction to remove cataracts from patients' eyes.[59]

- Systemic algebraic solution and completing the square: Al-Khwarizmi's popularizing treatise on algebra (The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing, c. 813–833 CE[60]: 171 ) presented the first systematic solution of linear and quadratic equations. One of his principal achievements in algebra was his demonstration of how to solve quadratic equations by completing the square, for which he provided geometric justifications.[61]: 14

- Thabit numbers: Named after Thabit ibn Qurra

- Throttling valve: It appears for the first time in the Banu Musa's Book of Ingenious Devices.[62]

- Variable structure control: Two-step level controls for fluids, a form of discontinuous variable structure controls, was developed by the Banu Musa brothers.[63]

- Wind-powered gristmill: The first wind-powered gristmills were built in the 9th and 10th centuries in what are now Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran.[58]

- Windpump: Windpumps were used to pump water since at least the 9th century in what is now Afghanistan, Iran and Pakistan.[64]

10th century

- Alhazen's problem: A theorem by ibn al-Haytham solved only in 1997 by Neumann.

- Arabic numerals: The modern Arabic numeral symbols originate from Islamic North Africa in the 10th century. A distinctive Western Arabic variant of the Eastern Arabic numerals began to emerge around the 10th century in the Maghreb and Al-Andalus (sometimes called ghubar numerals, though the term is not always accepted), which are the direct ancestor of the modern Arabic numerals used throughout the world.[65]

- Binomial theorem: The first formulation of the binomial theorem and the table of binomial coefficient can be found in a work by Al-Karaji, quoted by Al-Samaw'al in his "al-Bahir".[66][67][68]

- Cauchy-Riemann Integral: Ibn al-Haytham gave a simple form of this.[13]

- Decimal fractions: Decimal fractions were first used by Abu'l-Hasan al-Uqlidisi in the 10th century.[69][70]

- Experimental scientific method: Expounded and practised by ibn al-Haytham[71]

- Fountain pen: An early historical mention of what appears to be a reservoir pen dates back to the 10th century. According to Ali Abuzar Mari (d. 974) in his Kitab al-Majalis wa 'l-musayarat, the Fatimid caliph Al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah demanded a pen that would not stain his hands or clothes, and was provided with a pen that held ink in a reservoir, allowing it to be held upside-down without leaking.[72]

- Law of cotangents: This was first given by Ibn al-Haytham.[13]

- Muqarnas: The origin of the muqarnas can be traced back to the mid-tenth century in northeastern Iran and central North Africa,[73] as well as the Mesopotamian region.[74]

- Pascal's triangle: The Persian mathematician Al-Karaji (953–1029) wrote a now lost book which contained the first description of Pascal's triangle.[75][76][77]

- Ruffini-Horner Algorithm: Discovered by ibn al-Haytham[13]

- Sextant and mural instrument: The first known mural sextant was constructed in Ray, Iran, by Abu-Mahmud al-Khujandi in 994.[78]

- Shale oil extraction: In the 10th century, the Arab physician Masawaih al-Mardini (Mesue the Younger) described a method of extraction of oil from "some kind of bituminous shale".[79]

- Snell's law: The law was first accurately described by the Persian scientist Ibn Sahl at the Baghdad court in 984. In the manuscript On Burning Mirrors and Lenses, ibn Sahl used the law to derive lens shapes that focus light with no geometric aberrations.[80] According to Jim al-Khalili, the law should be called ibn Sahl's law.[81]

- Vertical-axle windmill: A small wind wheel operating an organ is described as early as the 1st century AD by Hero of Alexandria.[82][83] The first vertical-axle windmills were eventually built in Sistan, Persia as described by Muslim geographers. These windmills had long vertical driveshafts with rectangle shaped blades.[84] They may have been constructed as early as the time of the second Rashidun caliph Umar (634-644 AD), though some argue that this account may have been a 10th-century amendment.[85] Made of six to twelve sails covered in reed matting or cloth material, these windmills were used to grind grains and draw up water, and used in the gristmilling and sugarcane industries.[86] Horizontal axle windmills of the type generally used today, however, were developed in Northwestern Europe in the 1180s.[82][83]

11th-12th centuries

- Drug trial: Persian physician Avicenna, in The Canon of Medicine (1025), first described use of clinical trials for determining the efficacy of medical drugs and substances.[87]

- Double-entry bookkeeping system: Double-entry bookkeeping was pioneered in the Jewish community of the medieval Middle East.[88][89]

- Hyperbolic geometry: The theorems of Ibn al-Haytham (Alhacen), Omar Khayyám and Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī on quadrilaterals were the first theorems on hyperbolic geometry.[90]

- Magnifying glass and convex lens: A convex lens used for forming a magnified image was described in the Book of Optics by Ibn al-Haytham in 1021.[91]

- Mechanical flywheel: The mechanical flywheel, used to smooth out the delivery of power from a driving device to a driven machine and, essentially, to allow lifting water from far greater depths (up to 200 metres), was first employed by Ibn Bassal (fl. 1038–1075), of Al-Andalus.[92][93][94]

- Mercuric chloride (formerly corrosive sublimate): used to disinfect wounds.[year needed][95]

- Proof by contradiction: Ibn al-Haytham (965–1039) developed the method of proof by contradiction.[96]

- Spinning wheel: The spinning wheel was invented in the Islamic world by the early 11th century. There is evidence pointing to the spinning wheel being known in the Islamic world by 1030, and the earliest clear illustration of the spinning wheel is from Baghdad, drawn in 1237.[97]

- Steel mill: By the 11th century, much of the Islamic world had industrial steel watermills in operation, from Al-Andalus and North Africa to the Middle East and Central Asia.[98]

- Weight-driven clock: Arabic engineers invented water clocks driven by gears and weights in the 11th century.[99]

- Optic chiasm: The crossing of nerve fibres, and the impact on vision that this had, was first clearly identified by Persian physician "Esmail Jorjani", who appears to be Zayn al-Din Gorgani (1042–1137).[100] The optic chiasm was earlier theorized by Ibn al-Haytham in the early 11th century.[101]

- Pinhole camera: Ibn al-Haytham (965–1039), an Arab physicist also known as Alhazen, has been credited with the invention of the pinhole camera in the early 11th century.[102] The camera obscura effect described by Ibn al-Haytham became the subject of many experiments over the centuries, mainly in dark rooms with a small opening in shutters, to study the nature of light and to safely watch solar eclipses.[citation needed] The camera obscura or pinhole image is a natural optical phenomenon. Early known descriptions are found in the Chinese Mozi writings (circa 500 BCE) and the Aristotelian Problems (circa 300 BCE – 600 CE).[citation needed]

- Paper packaging: The earliest recorded use of paper for packaging dates back to 1035, when a Persian traveler visiting markets in Cairo noted that vegetables, spices and hardware were wrapped in paper for the customers after they were sold.[103]

- Bridge mill: The bridge mill was a unique type of watermill that was built as part of the superstructure of a bridge. The earliest record of a bridge mill is from Córdoba, Spain in the 12th century.[104]

13th century

- Fritware: It refers to a type of pottery which was first developed in the Near East, beginning in the late 1st millennium, for which frit was a significant ingredient. A recipe for "fritware" dating to c. 1300 AD written by Abu’l Qasim reports that the ratio of quartz to "frit-glass" to white clay is 10:1:1.[105] This type of pottery has also been referred to as "stonepaste" and "faience" among other names.[106] A 9th-century corpus of "proto-stonepaste" from Baghdad has "relict glass fragments" in its fabric.[107]

- Mercury clock: A detailed account of technology in Islamic Spain was compiled under Alfonso X of Castile between 1276 and 1279, which included a compartmented mercury clock, which was influential up until the 17th century.[108] It was described in the Libros del saber de Astronomia, a Spanish work from 1277 consisting of translations and paraphrases of Arabic works.[109]

- Mariotte's bottle: The Libros del saber de Astronomia describes a water clock which employs the principle of Mariotte's bottle.[108]

- Metabolism: Although Greek philosophers described processes of metabolism, Ibn al-Nafees is the first scholar to describe metabolism as "a continuous state of dissolution and nourishment".[110]

- Naker: Arabic nakers were the direct ancestors of most timpani, brought to 13th-century Continental Europe by Crusaders and Saracens.[111]

Al Andalus (Islamic Spain)[edit]

9th-12th centuries

14th century

- Hispano-Moresque ware: This was a style of Islamic pottery created in Arab Spain, after the Moors had introduced two ceramic techniques to Europe: glazing with an opaque white tin-glaze, and painting in metallic lusters. Hispano-Moresque ware was distinguished from the pottery of Christendom by the Islamic character of its decoration.[122]

- Polar-axis sundial: Early sundials were nodus-based with straight hour-lines, indicating unequal hours (also called temporary hours) that varied with the seasons, since every day was divided into twelve equal segments; thus, hours were shorter in winter and longer in summer. The idea of using hours of equal time length throughout the year was the innovation of Abu'l-Hasan Ibn al-Shatir in 1371, based on earlier developments in trigonometry by Muhammad ibn Jābir al-Harrānī al-Battānī (Albategni). Ibn al-Shatir was aware that "using a gnomon that is parallel to the Earth's axis will produce sundials whose hour lines indicate equal hours on any day of the year." His sundial is the oldest polar-axis sundial still in existence. The concept later appeared in Western sundials from at least 1446.[123][124]

Sultanates[edit]

12th century

13th century

- Various automatons: Al-Jazari's inventions included automaton peacocks, a hand-washing automaton, and a musical band of automatons.[127][128][129]

- Camshaft: The camshaft was described by Al-Jazari in 1206. He employed it as part of his automata, water-raising machines, and water clocks such as the castle clock.[130]

- Candle clock with dial and fastening mechanism: The earliest reference of the candle clock is described in a Chinese poem by You Jiangu (AD 520), However the most sophisticated candle clocks known, were those of Al-Jazari in 1206.[131] It included a dial to display the time.[132]

- Crankshaft: Al-Jazari (1136–1206) is credited with the invention of the crankshaft.[29] He described a crank and connecting rod system in a rotating machine in two of his water-raising machines.[133] His twin-cylinder pump incorporated a crankshaft,[134] including both the crank and shaft mechanisms.[135]

- Crank-slider: Ismail al-Jazari's water pump employed the first known crank-slider mechanism.[136]

- Cotton gin with worm gear: The worm gear roller gin was invented in the Delhi Sultanate during the 13th to 14th centuries.[137]

- Design and construction methods: English technology historian Donald Hill wrote, "We see for the first time in al-Jazari's work several concepts important for both design and construction: the lamination of timber to minimize warping, the static balancing of wheels, the use of wooden templates (a kind of pattern), the use of paper models to establish designs, the calibration of orifices, the grinding of the seats and plugs of valves together with emery powder to obtain a watertight fit, and the casting of metals in closed mold boxes with sand."[138]

- Draw bar: The draw bar was applied to sugar-milling, with evidence of its use at Delhi in the Mughal Empire by 1540, but possibly dating back several centuries earlier to the Delhi Sultanate.[139]

- Minimising intermittence: The concept of minimising the intermittence is first implied in one of Al-Jazari's saqiya devices, which was to maximise the efficiency of the saqiya.[140]

- Programmable automaton and drum machine: The earliest programmable automata, and the first programmable drum machine, were invented by Al-Jazari, and described in The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, written in 1206. His programmable musical device featured four automaton musicians, including two drummers, that floated on a lake to entertain guests at royal drinking parties. It was a programmable drum machine where pegs (cams) bump into little levers that operated the percussion. The drummers could be made to play different rhythms and different drum patterns if the pegs were moved around.[141]

- Tusi couple: The couple was first proposed by Nasir al-Din al-Tusi in his 1247 Tahrir al-Majisti (Commentary on the Almagest) as a solution for the latitudinal motion of the inferior planets. The Tusi couple is explicitly two circles of radii x and 2x in which the circle with the smaller radii rotates inside the Bigger circle. The oscillatory motion be produced by the combined uniform circular motions of two identical circles, one riding on the circumference of the other.

- Griot: The griot musical tradition originates from the Islamic Mali Empire, where the first professional griot was Balla Fasséké.[142]

- Segmental gear: A segmental gear is "a piece for receiving or communicating reciprocating motion from or to a cogwheel, consisting of a sector of a circular gear, or ring, having cogs on the periphery, or face."[143] Professor Lynn Townsend White, Jr. wrote, "Segmental gears first clearly appear in al-Jazari".[144]

- Sitar: According to various sources, the sitar was invented by Amir Khusrow, a famous Sufi inventor, poet, and pioneer of Khyal, Tarana and Qawwali, in the Delhi Sultanate.[145][146] Others say that the instrument was brought from Iran and modified for the tastes of the rulers of the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire.[146]

14th century

Ottoman Empire[edit]

14th century

15th century

- Coffee: Although there is early historical accounts of coffee consumption ( as qahwa) in Ethiopia, it is not clear whether it was "used" as a beverage.[150] The earliest historical evidence of coffee drinking appears in the middle of the 15th century, in the Sufi monasteries of the Yemen in southern Arabia.[151][152] From Mocha, coffee spread to Egypt and North Africa,[153] and by the 16th century, it had reached the rest of the Middle East, Persia and Turkey. From the Muslim world, coffee drinking spread to Italy, then to the rest of Europe, and coffee plants were transported by the Dutch to the East Indies and to the Americas.[154]

- Dardanelles Gun: The Dardanelles Gun was designed and cast in bronze in 1434 by Munir Ali. The Dardanelles Gun was still present for duty more than 340 years later in 1807, when a Royal Navy force appeared and commenced the Dardanelles Operation. Turkish forces loaded the ancient relics with propellant and projectiles, then fired them at the British ships. The British squadron suffered 28 casualties from this bombardment.[155]

- Iznik pottery: Produced in Ottoman Turkey as early as the 15th century AD.[156] It consists of a body, slip, and glaze, where the body and glaze are "quartz-frit."[157] The "frits" in both cases "are unusual in that they contain lead oxide as well as soda"; the lead oxide would help reduce the thermal expansion coefficient of the ceramic.[158] Microscopic analysis reveals that the material that has been labeled "frit" is "interstitial glass" which serves to connect the quartz particles.[159]

- Standing army with firearms: The Ottoman military's regularized use of firearms proceeded ahead of the pace of their European counterparts. The Janissaries had been an infantry bodyguard using bows and arrows. During the rule of Sultan Mehmed II they were drilled with firearms and became "the first standing infantry force equipped with firearms in the world."[160]

16th century

Safavid Dynasty[edit]

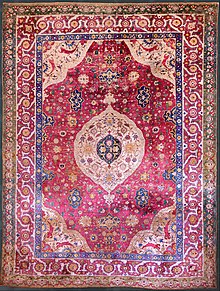

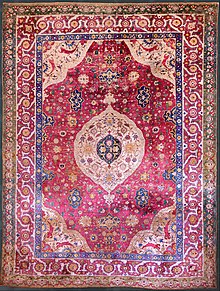

The Rothschild Small Silk Medallion Carpet, mid-16th century,

Museum of Islamic Art, Doha

15th century

- Classical Oriental carpet: By the late fifteenth century, the design of Persian carpets changed considerably. Large-format medallions appeared, ornaments began to show elaborate curvilinear designs. Large spirals and tendrils, floral ornaments, depictions of flowers and animals, were often mirrored along the long or short axis of the carpet to obtain harmony and rhythm. The earlier "kufic" border design was replaced by tendrils and arabesques. All these patterns required a more elaborate system of weaving, as compared to weaving straight, rectilinear lines. Likewise, they require artists to create the design, weavers to execute them on the loom, and an efficient way to communicate the artist's ideas to the weaver. Today this is achieved by a template, termed cartoon (Ford, 1981, p. 170[168]). How Safavid manufacturers achieved this, technically, is currently unknown. The result of their work, however, was what Kurt Erdmann termed the "carpet design revolution".[169] Apparently, the new designs were developed first by miniature painters, as they started to appear in book illuminations and on book covers as early as in the fifteenth century. This marks the first time when the "classical" design of Islamic rugs was established.[170]

Mughal Empire[edit]

16th century

A detailed portrait of the

Mughal Emperor Jahangir holding a globe probably made by Muhammad Saleh Thattvi

- Hookah or water pipe: according to Cyril Elgood (PP.41, 110), the physician Irfan Shaikh, at the court of the Mughal emperor Akbar I (1542–1605) invented the Hookah or water pipe used most commonly for smoking tobacco.[171][172][173][174]

- Metal cylinder rocket: In the 16th century, Akbar was the first to initiate and use metal cylinder rockets known as bans, particularly against war elephants, during the Battle of Sanbal.[175]

- Multi-barrel matchlock volley gun: Fathullah Shirazi (c. 1582), a Persian polymath and mechanical engineer who worked for Akbar, developed an early multi-shot gun. Shirazi's rapid-firing gun had multiple gun barrels that fired hand cannons loaded with gunpowder. It may be considered a version of a volley gun.[176] One such gun he developed was a seventeen-barrelled cannon fired with a matchlock.[177]

- Seamless celestial globe: It was invented in Kashmir by Ali Kashmiri ibn Luqman in 998 AH (1589–1590), and twenty other such globes were later produced in Lahore and Kashmir during the Mughal Empire. Before they were rediscovered in the 1980s, it was believed by modern metallurgists to be technically impossible to produce metal globes without any seams.[178]

17th century